FAQs

-

Who got you interested in photography?

My father was an Air Force pilot and photographer. After WWII, having sustained a broken back in a crash landing that prohibited him from piloting any longer, he workrd as a photogrammetrist for the Aeronautical Chart and Information Center in St. Louis, which later became the Defense Mapping Agency, and is today known as the NGA (National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency). He retired from there, but was also active as a wedding and event photographer for years – so we always had a darkroom in our basement. My dad pushed me towards photography. Like most kids, I developed other interests and began to resist his tutelage.

But, later, after I enlisted in the U.S. Air Force during the Vietnam War and had the opportunity to see new places and experience new cultures, my interest in photography returned and has stayed with me up until today.

However, while I’ve enjoyed making photos during my Air Force career (personal work and for the USAF Office of Information), my post-military career was in advertising, public relations, journalism, and corporate communications. At the time of my retirement, I was the Communications Director for the Bar Association of Metropolitan Saint Louis. In that position, I oversaw public information for that non-profit and published a monthly magazine, contributed to their website, documented special events and the association’s achievements with lawyers, judges and the public. But, here too, I used photography, in addition to my writing, editing, design, and promotional skills to achieve the organization’s public information goals.

I’ve never considered myself a professional photographer, though I have done for hire work for many years. It was never my sole source of income. And, for me, not relying solely on photography for my livelihood provided a certain amount of freedom to take it in any direction I wanted.

In my capacity as an advertising director, I often functioned as the art director/creative director on print projects of all sizes and types, and was fortunate to hire some of the best St. Louis-based commercial photographers. Working with them and watching them tackle difficult product and advertising shoots taught me loads that I was able to utilize later in my personal editorial photography efforts.

-

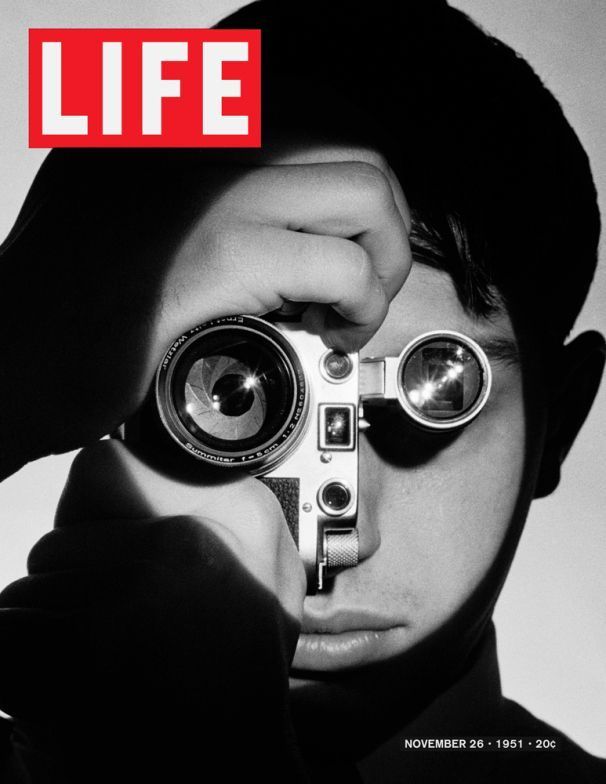

What were your first cameras?

There were two in particular. First, was a 2-1/4 x 3-1/4 Graflex Crown Graphic. My dad was. using a 4x5 Graflex back then and found this almost new “smaller” version for me. I used it to learn how to shoot weddings and do my first school yearbook work in middle and high school.

I also acquired a German Baldina 35mm rangefinder camera, a poor man’s Leica, with a fixed 50mm lens. It made good quality images and was very compact.

Later, shortly after enlisting in the Air Force, I purchased a used Nikkormat 35mm camera with two lenses (50mm and 105mm) that began a life-long preference for Nikons — though years later I would also purchase a used Leica M9 digital and now own and use a Leica M10 from time to time.

-

Why is so much of your work centered around civil rights and protest photography?

I blame this on my mom. She was always aware of and interested in the lack of equal justice in the United States, having been a first generation Italian immigrant. As a young woman she experienced prejudice in many forms, including misogyny and hiring biases. She was also active in her church and took me to one of the early civil rights protests at a small amusement park near the St. Louis airport when I was only 14 years old. The amusement park at that time denied entry to African Americans. Since then, I’ve come to understand the scope of racial injustice in St. Louis and across the United States through research, reading, and actual life experiences. So it has become one of my passions and I have applied my photography to that cause. From my tenure with the Bar Association of Metropolitan Saint Louis, I became familiar with two non-profit law firms: Legal Services of Eastern Missouri and ArchCity Defenders. Both provide free legal representation to those in need and unable to afford their own legal resources. As a result, over the years, I have worked with both of these non-profits to help with their photographic needs — documenting their work, helping with development efforts, and more.

-

What’s the deal with your landing page headline, “exPOSED”?

It’s a play on words; a combination of “exposed” and “from posed” — from film days when we “exposed” film, and from what comprises my body of work, which tends to be candid for the most part, but also sometimes “posed”.

-

What camera gear do you use and why?

That’s a question whose answer I find somewhat irrelevant to what we try to do with photography, if you are serious about it. I know many photographers who have camera gear that is not as high-end or expensive as mine, but capture exceptionally excellent images on a regular basis. I believe it is not the camera, but the photographer that is most important in making memorable photographs.

That said, I’ve mentioned above that I have been a Nikon user since 1968. I’ve stayed with Nikon for their dependability, and frankly, because once you invest in multiple bodies and lenses, it is difficult to switch brands. Currently, I own and use two Nikon D850s and a Nikon Z8. I have lenses ranging from 18mm to 300mm, including several zoom lenses (16-28mm, 35-150mm, and 80-200mm). I do not own a prime 50mm. Also in the stable is a Leica M10 that I use when the subject requires me to be less conspicuous and I am seeking the color-grading that the Leica sensor offers. However, working with the Leica is slower as everything is manual – no autofocus, or autoexposure.

In addition to the camera bodies mentioned, I own five speedlghts and use Pocket Wizard triggers and some light modifiers (umbrellas, softboxes, etc.) from time to time. I’ve also used a couple of LED light sources from time to time. All these mostly for portraiture and indoor architectural photography. I donated my studio lights to a local university’s photography department several years ago since I rarely used them and the university didn’t have the budget to. purchase their own.

-

Who are some photographers whose work you admire and follow?

Yeah, I have a rather eclectic list that starts with British photographer David Nightingale for his technique and landscapes and street photography. Joe McNally for his sense of lighting and big picture fearlessness. Plus he is one of the few who has mastered the creative and the technical sides of this art completely, in my opinion. Larry Burrows (deceased) Time/Life photographer who I met in Bangkok quite by accident in 1971 and was the epitome of what a combat photographer should be.

Then there is Bob Kolbrener, an acolyte of Ansel Adams, who did work for me when I was a cub advertising guy and he was soul searching how to leave his world of being a local commercial photographer and make the leap to glorius B&W landscapes out West to pursue his artistic dream, which he did and did quite well,

Turkish and Magnum photographer Emin Özmen. A fearless photojournalist whose work reflects the state of turmoil and what happens in a country with such great promise and wonderful cultures succumbs to autocracy. His coverage of the recent earthquakes in Turkey, the Syrian revolutions and immigration into Turkey, the Kurdish fight for freedom, and economic instability that results from greedy autocratic politics, and the effects of famines worldwide make up his body of work.

Matika Wilbur, author of Project 562, a 10-year effort and journey throughout the United States (all 50 states) where she met, interviewed, photographed, and explored the lives of today’s indigenous Americans. The “562” in her project’s name refers to the number of federally-recognized tribes, urban Native communities that exist today. A Native American herself, so much empathy exudes from her writings and images to help us understand the past and future of Native Americans. Her dedication to this project literally meant that she packed up everything, picked up and hit the road in an old van — and kept at it for 10 years until all 562 tribes had been visited and studied. Her photographs span medium format film days to more current digital photography work. It’s all excellent and very personal. A must read because if you are not and indigenous American, you are an immigrant. Something many of us have forgotten.

-

What would you change about your career if you could?

In hindsight, I would have pursued more photographic and editorial work, telling stories with dramatic images for either a newspaper or magazines. Of course, those opportunities hardly exist anymore, right? And, one’s vision for the future is not always clear in your youth. Regrets though? Few.

When I was completing my four-year enlistment in the U.S. Air Force, I had three opportunities for employment. First was to re-enlist in the USAF. While I was somewhat adverse to the regimentation of military life, the idea of discovering new places, living in foreign lands, and always ready for the next adventure appealed to me. And there was a re-enlistment bonus and a rank promotion in the offing.

My last duty assignment was in Little Rock, Arkansas, and one of the local papers there had offered me a job as a photojournalist after seeing my work with the base’s Office of Information and in the base newspaper. That job was extremely appealing to me, but it would have caused problems with my family life at the time.

The third option is the one I took: to return to the small ad agency I had worked at before enlisting. While it offered a wide range of future possibilities in advertising, that choice reduced my ability to pursue a more creative and meaningful career with photography.

This is a good place to also mention that while I was fundamentally opposed to the Viet Nam War for many reasons (moral, economic and political), I enlisted because I saw it is my duty to Country and to honor the service of my father and his father before him. It was a compromise. Again, would I do that again? Not sure. Probably not.

-

What is "woke" and how does it relate to your photography?

"Woke is an adjective derived from African-American Vernacular English (AAVE) meaning "alert to racial prejudice and discrimination". Beginning in the 2010s, it came to encompass a broader awareness of social inequalities such as racial injustice, sexism, and denial of LGBT rights. Woke has also been used as shorthand for some ideas of the American Left involving identity politics and social justice, such as white privilege and reparations for slavery in the United States."

— Source: Wikipedia.

For me, as a photographer, "woke" means I apply an objective and curious view of social and racial situations as I confront them in my work. I also take the time to study and understand factual history before forming an opinion – reading, observing, discussing, listening, and consulting multiple sources of information. I try to understand situations I encounter, apply empathy, push away implicit biases, and work to record the truth as I see it. This is the best we can all do. I don't allow others' dog whistles of hate, bigotry, or racism to filter into my work.

In essence, being "woke" is a matter of opening your hearts and minds to the true experiences of others – good or bad.